Bde Maka Ska, the indigenous name for Lake Calhoun, was reclaimed because of a reckoning with history. Society is going through a focused period of expanding awareness, reflection and awakening.

The public art created for Nicollet reveals diverse histories and realities. Many of the visual artists and writers create work that speaks passionately from their personal reality and beliefs – as an indigenous person, member of the LGBTQIA community, person of color, religious person, or a life-long or brand-new citizen of Minneapolis.

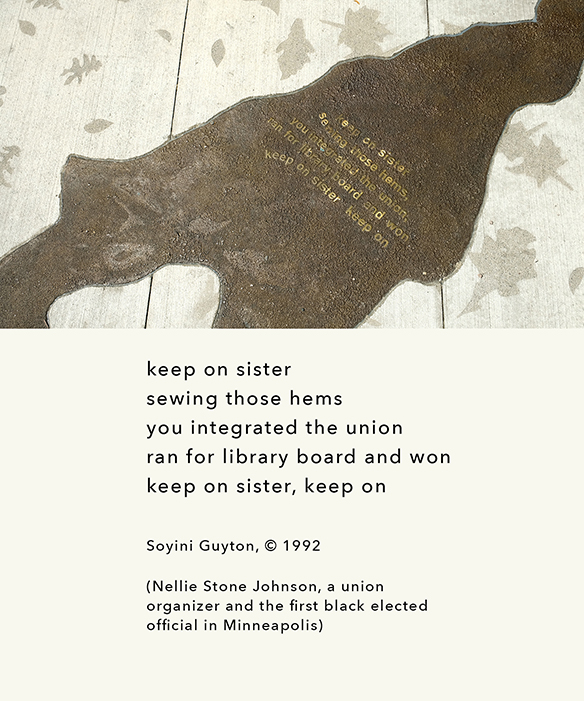

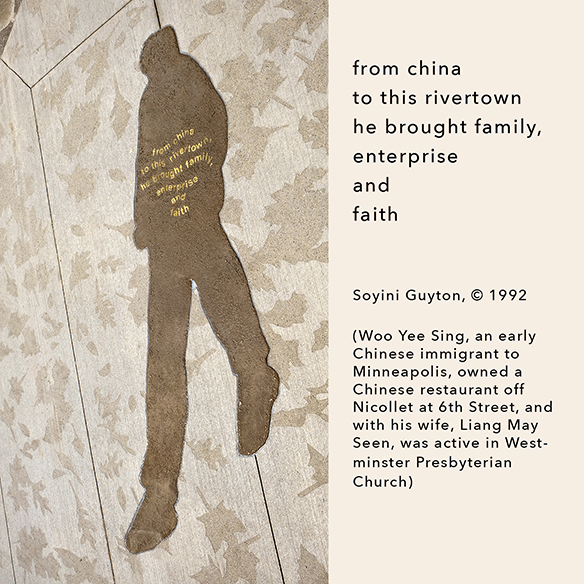

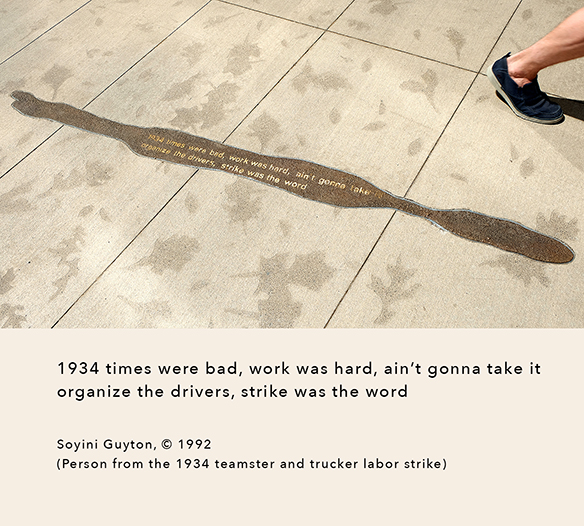

But sometimes we miss the intention and meaning of the art in front of us – or in the case of the cast bronze pavement insets of Shadows of Spirit – beneath our feet. Created in 1992 by visual artists Seitu Jones and Ta-coumba Aiken with poems by Soyini Guyton, the shadows, some elongated and distorted and others recognizable, honor the ghosts of our ancestors.

Brief evocative poetic texts imprinted on the shadows refer to seven people who are part of the story of Minneapolis – Nellie Stone Johnson, a union organizer and the first black elected official in Minneapolis; Woo Yee Sing, an early Chinese immigrant to Minneapolis, who owned a Chinese restaurant off Nicollet at 6th Street, and with his wife, Liang May Seen, was active in Westminster Presbyterian Church; a settler of the Bohemian Flats, a low-lying area on the west bank of the Mississippi, settled primarily by Eastern European immigrants from the 1860s-1930s; writer Meridel LeSueur, a 20th century writer and community activist; Dred Scott, an African-American man who was enslaved and sued the Supreme Court for his freedom and the freedom of his wife, Harriet Robinson; and Aŋpetu Sapa Wiŋ (Dark Day Woman), a member of the Dakota Tribe, who according to legend, took her life by paddling a canoe over St. Anthony Falls.

At the start of Nicollet’s construction, all of the public art had to be removed. To determine which artwork should return to Nicollet, the City conducted an on-the-street survey of random passersby in the area near each piece before it was removed. The response to Shadows of Spirit located between 11th Street and Grant Street was disappointing. When asked specific questions about the work, 27% said it didn’t contribute to community; 26% said it didn’t contribute to place; and 44% said they wouldn’t miss it if it were gone. It became apparent that the public misperceived and misunderstood this important work.

According to the artists, when they installed Shadows of Spirit in 1992, the City had a policy against identifying individuals in artworks. So for all the years since, the public has had no way to interpret the intentions and meaning of the shadows because they didn’t know who or what the brief poetic texts on each of them referred to.

Over time, with awareness comes change. Concurrent with the reinstallation of Shadows of Spirit, the City has produced an online interactive map about all of the public art on Nicollet and with details about each shadow and the person it honors. Also the purpose of the blog you are reading and this website has been to reveal the intent and creative process behind all of Nicollet’s new and returning public art, including Shadows of Spirit, with stories about the work and the artists, often in their own words.

When you stroll the length of Nicollet, experience the public art and reference the interactive map or the website, you may realize that a majority of the work is by artists of color including Shadows of Spirit by Seitu Jones, Ta-coumba Aiken and Soyini Guyton; Enjoyment of Nature by Kinji Akagawa; Nimbus (coming in spring 2018) by Tristan Al-Haddad; Nicollet Lanterns by Blessing Hancock with poems by writers of color Moheb Soliman, Sagirah Shahid, Junauda Petrus and R. Vincent Moniz, Jr. (Nu’Eta); and Tableau, A Native American Mosaic by renown Ojibwe artist George Morrison (to be reinstalled spring 2018).

Public art’s intentions and roles are complex – to empower new voices, challenge, prod, inform, delight, inspire awe, foster empathy, be functional, useful, beautiful, a counterpoint to urban settings, blend with urban settings, explore new forms and materials, create places, promote public gathering and sociability, stimulate controversy or reveal forgotten histories. The public art on Nicollet reflects the breadth and depth of public art, the diversity of makers and their realities, and expresses our city’s cultural vitality.

View a photo essay about the re-installation of Shadows of Spirit and an interview with the artists here.