Friday, September 7, 2020

Installation began after Labor Day and progressed slowly during the first week with about one-fourth of the pattern set.

Slurry mix is scrubbed into the pervious concrete base and loose damp granular mortar mix laid over it.

Then the slurry mix is also applied to the back of the granite paver, and it is laid in place and tamped down.

September 11, 2020

The following Tuesday morning, many granite pieces were ready to be set. A stretch of sunny, but hot, days were predicted, so the team led by master mason Mike Schermerhorn with Henry Kisumu, Jake Nelson, Adam Pettit, Rob Williams and Steve Violet, and conservator Kristen Gillette, got busy.

It is truly a privilege to work with master mason Mike Schermerhorn. This is the fourth time he has worked on the mosaic, and each time he brings tremendous expertise and great care and precision. He knows this mosaic very, very well. - Conservator Kristin Cheronis

September 14, 2020

By Friday afternoon of the second week, great progress had been made. Almost two-thirds of the mosaic had been set and the site, cleaned up and locked down for the weekend.

September 28, 2020

Two weeks later, after some stops and starts because of rainy weather, setting was complete and grouting the mosaic was underway.

George Morrison’s Artistic Journey

Morrison was born in 1919 on Lake Superior’s North Shore near Grand Marais, Minnesota. Upon his retirement in 1983 he moved back to Grand Portage, where he continued to create drawings, paintings and wood collages. His later works include the horizon paintings for which he is most well known, but also his totems and the design for Nicollet’s granite mosaic.

Between his departure from and return to the North Shore, Morrison studied in in New York at the Art Students League and in Paris, and during the 1940s-1950s, spent summers near the ocean in Provincetown, Massachusetts. He taught at the Rhode Island School of Design, then the Minneapolis College of Art, and Design and finally at the University of Minnesota (American Indian studies and studio arts, 1970-1983).

Landscape, a woodcut (relief) print from 1950 is one of the earliest examples of Morrison’s use of faceting applied to a landscape subject that was later expressed in his wood collages, totems, and the Nicollet mosaic. In a handwritten note from 1979, Morrison says this woodcut was “one of the beginnings of my own semi-abstract art works and is also good evidence of the persistence of the landscape theme in my work – with ‘mosaic sections,’ and ‘horizon’ suggestions.”

George Morrison, Landscape, 1950, woodcut on paper, 13″ x 16″ is an example of the artist’s use of faceting; breaking down larger areas into smaller subdivisions. (Collection Walker Art Center, Minneapolis. T.B. Walker Acquisition Fund, 1951.)

The Nicollet mosaic is related to his wood collages of the 1970s-80s that Morrison described as “paintings in wood.” Composed intuitively, he explained the collages were “derived from nature, based on landscape…. driftwood gives a sense of history – wood that has a connection to earth, yet has come from the water.” Although he made the first of the wood collages on the East Coast, he acknowledged that the collages may have been inspired subconsciously by the rock formations on the North Shore.

Morrison called his wood collages “paintings in wood.” This Untitled (1975) collage is in the collection of the Minnesota Historical Society and reproduced with their permission.

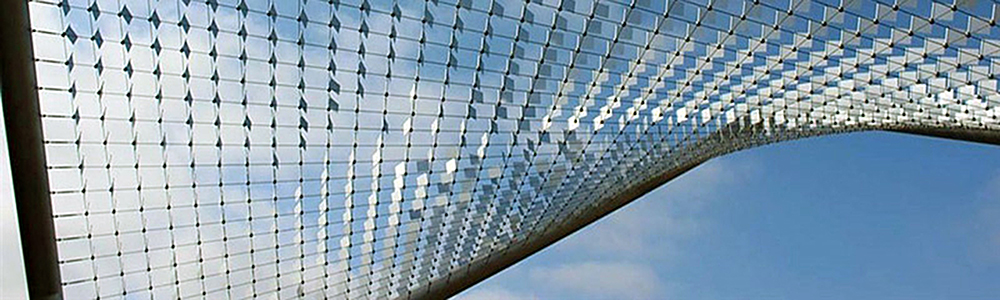

Around the time of the 1992 Nicollet Mall commission, Rob Silberman wrote in his essay “A Long Look at the Art of George Morrison,” that the artist has a “longstanding concern with faceting, with breaking down large areas into smaller divisions, almost like taking a single image and dividing it into jigsaw-puzzle shapes… each piece of wood is separated by spaced from its neighbor in a manner resembling both a mosaic and a drawing (the spaces read as both gaps and lines).”

Kristin Makholm is the Executive Director of the Minnesota Museum of American Art in Saint Paul which has extensive holdings of Morrison’s work. She observes that, “Morrison often takes one idea or concept and spins it out in collages, prints, small sculptures and totems – there is a homogeneity in the surface [qualities] even though he works in various media.” The comparison between Red Cube, a lithograph of 1983 and the La Salle Plaza Totem of 1991 is instructive. This same formal language was applied to the Nicollet Mall mosaic, although in an entirely different material – granite – and with a process that involved a fabricator (Cold Spring Granite).

Red Cube, 1983, color lithograph, 19 x 19 inches, Collection Minnesota Museum of American Art, Gift of Saint Paul Academy and Summit School, 87.14.1

Makholm points out that, “during the 1970s-80s, Morrison sees that his work could connect to the community and to a public context. He applied the collage concept to public art. Morrison’s public work had a sensitivity to the environment that it must work in, and to Nicollet Mall.”

Morrison drew a connection between his totems, the Nicollet Mall mosaic, and Native American imagery. He remarked, “each totem has a different feel to it. The best example is in the lobby of the La Salle Plaza in downtown Minneapolis. It’s twenty-one feet high and two feet square…. I stained the lighter woods with color, trying to maintain certain Indian colors – red, blue, yellow, and some green. I deliberately did it that way and employed some animal, bird, weather, and plant imagery – a beaver, for instance, and some leaves, along with a lightning bolt and suggestions of water or clouds. Not realistic, but semi-abstract interpretations of these elements. It makes for a very active and colorful totem…. [The La Salle Plaza Totem] is about two blocks from my granite mosaic on Nicollet Mall. I designed the mosaic and the city had it constructed, with fourteen variations of tone from light to dark. I put some Indian suggestions in the 200 pieces, but they are somewhat lost in the abstract design.”

Morrison’s La Salle Plaza Totem,

Minneapolis, 1991.

Complex Identity

Standing in the Northern Lights is the Indian name given to Morrison by a tribal elder. Although he embraced his background, throughout his career Morrison was concerned about being stereotyped as a Native American artist. In his autobiography Turning the Feather Around, My Life in Art, he recounts that Patricia Hobot, a Lakota who was gallery director at the Minneapolis American Indian Center [where Morrison created the wood construction for the exterior of the building] said this about his wood collages: “People often want something that is stereotypical Indian and involves racial stereotyping, …but George’s work embodies the abstract values of the Indian people…. His use of pieces to make up a whole is very Indian. It shows respect for individuality but indicates how the individual is expected to fit into the whole.”

Wood construction created by Morrison in 1974-75 distinguishes the facade of The American Indian Center, Minneapolis.

Morrison thought those were good connections that Hobot made. He responded, “the basis of all art is nature; it creeps into even abstract art. The look of the North Shore was subconsciously in my psyche, prompting some of my images.”

W. Jackson Rushing III writes in Modern Spirit, The Art of George Morrison, a catalog accompanying a major retrospective of the artist’s work that, “Morrison stuck with the surrealist process [relying on intuition, improvisation and chance, discovering forms and images while working] for fifty-plus years because it was an existential one, which stressed generating visionary content out of the subconscious, and thus enabling him – not the critics or his peers – to be the author of his own identity…. The creative process allowed Morrison to become real, to both self-discover and self-invent…Therefore, how could anything but “Indian” come through?”

Morrison has said that, “if there’s any ‘Indian’ coming through it’s because I am an Indian…. I think these responses [to nature and materials] become part of the inner self, springing from a combination of many things, perhaps from my early background in northern Minnesota – that in combination with Cape Cod, which is more expansive in terms of space and light, sea and sky, and with living and working in New York.”

Lasting Legacy

Morrison died on April 17, 2021 at the age of eighty. His work continues to be exhibited and evaluated. In 2004, “Native Modernism,” the inaugural exhibition of the Smithsonian Museum of the American Indian in Washington, DC featured Morrison’s work along with that of Allan Houser. Curator Truman Lowe wrote, “Morrison and Houser ushered in a new, modernist era in Native art history, in which identification with a uniform Indian aesthetic gave way to a greater freedom for personal experimentation and expression.”

“Modern Spirit, The Art of George Morrison”, a major retrospective, toured the country with its last stop at the Minnesota History Center, Saint Paul in 2015.

See Morrison’s work in the archive of the Minnesota Museum of American Art.

Sources:

Lowe, Truman. Native Modernism: The Art of George Morrison and Alan Houser. Washington DC: Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian, 2004.

Kristin Makholm interview, December 17, 2014.

Morrison, George and (introduction by) Galt, Margot Fortunato. Turning the Feather Around: My Life in Art. Minnesota: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1998.

Rushing, W. Jackson, III and Kristin Makholm. Modern Spirit, the Art of George Morrison. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, in cooperation with the Minnesota Museum of Art, 2013.

Silberman, Rob. “A Long Look at the Art of George Morrison.” Artpaper, September, 1990.

Vizenor, Gerald. “George Morrison, Anishinaabe Expressionist Artist.” American Indian Quarterly, (vol. 3, No. 03 & 4, 2006).