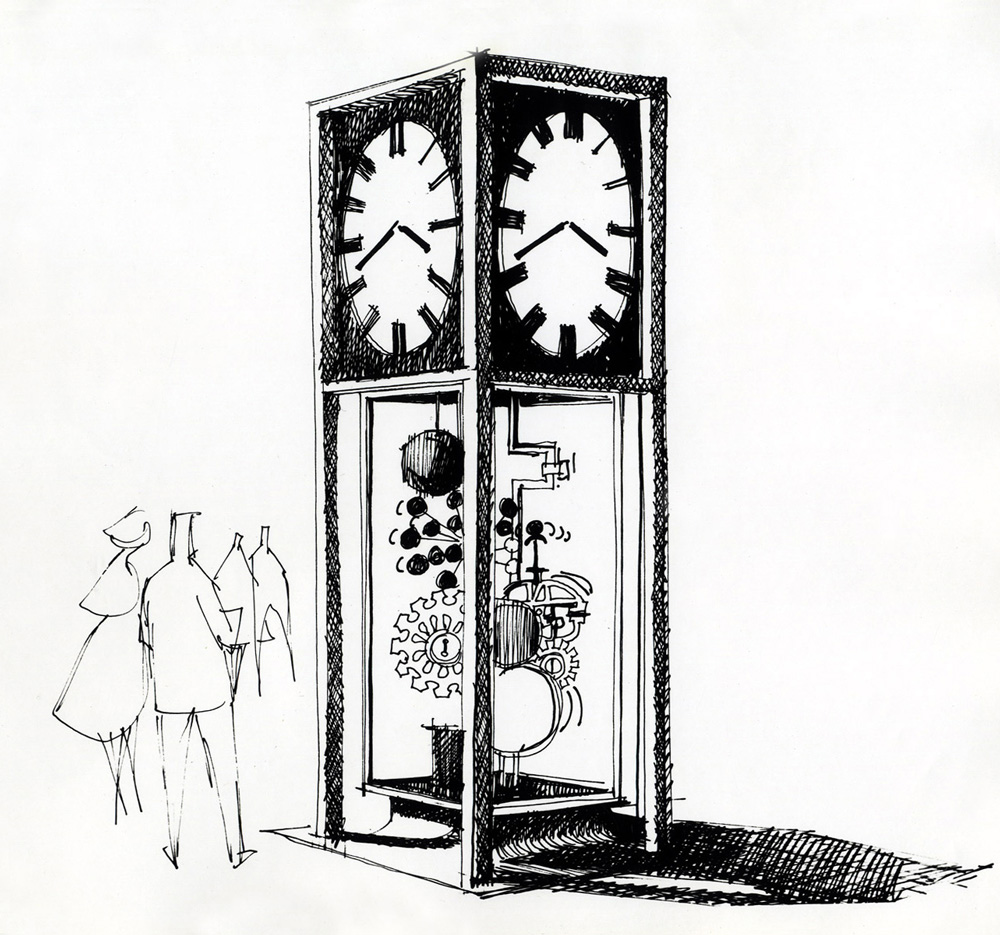

Sculpture Clock, 1960s, Nicollet Mall, Minneapolis, Minnesota. Jack Nelson

Photo courtesy of the Halprin Archive at the University of Pennsylvania.

Introducing Jack Nelson, Creator of the Sculpture Clock

Jack Nelson, eclectic artist and part of the Experimental Studios in the College of Art at Syracuse University, Syracuse, New York, was involved in the creation of the Sculpture Clock originally located in front of the Young-Quinlan Building at Ninth Street and Nicollet Avenue when it was dedicated on October 7, 1968. Most recently it was sited on the southeast corner of Eleventh Street near Peavey Plaza in front of Orchestra Hall.

Educated at the Art Institute of Chicago, Nelson worked in media ranging from drawing and sculpture to performance and video, and was a teacher who inspired a generation of multi-media artists including renowned video installation artist Bill Viola who studied under him. Syracuse University was among the first research universities to address the need to prepare new generations of artists to make full use of the new tools at hand including photography, video and film. “They took a chance and hired some new blood for the faculty, including my advisor Jack Nelson. They took a look at the curriculum and said we need something more creative, dynamic, and contemporary,” says Viola.

Nelson was known primarily for his kinetic sculptural assemblages. From approximately 1959-1972, he had annual solo shows at New York City galleries often reviewed in ARTNews. Arline J. Meyer described his work at New Directions gallery in the November 1959 issue of the journal: “Jack Nelson’s machines are linear structures of slim, soldered metal rods. Various parts are set in motion by either a small crank or by a lifted pin which sets a battery activating a system of pulleys.” During the 1960s, his work became increasingly figurative; he added doll parts, bisque heads, stuffed birds, and miscellaneous junk according to reviewers, and the work often had buttons that activated bells and colored lights.

Lawrence Campbell, reviewing a 1972 show at Krasner Gallery, called Nelson “an inventor of Surrealist motorized kinetic sculptures and toys, also a maker of constructions and assemblages, also a display virtuoso.” The works had also recently been exhibited at the Everson Museum, Syracuse, New York, and Campbell described them as, “all hanging wall objects, or standing objects with lids which open like coffins, or perhaps they are like slot machines? In all these works a face looks out, dead center, like a death mask, and sometimes, were it not for the eyes and mouths and other parts of the face cut out from magazines and glued on, these faces would look as though blown up with bicycle pumps and not like real faces. Actually they are made out of a white plastic, and the rest of the works are made of stitched, bleached linen mounted on wood. There are frequent references to the moon in the form of a face silhouetted within a crescent, like a famous French commercial trade mark. As remarkable as these works are, they somehow manage to miss the boat. Perhaps Nelson has too many interests…. The impression that remains is of an ingenuous and skilled craftsman.”

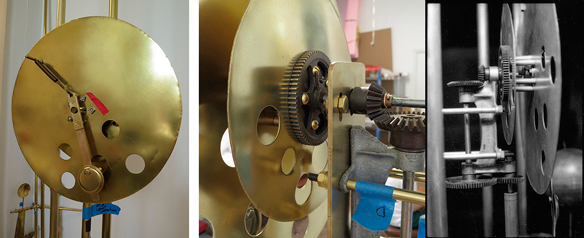

Sculpture Clock by Jack Nelson. Detail

Photo courtesy of the Halprin Archive at the

University of Pennsylvania.

Nelson and Lawrence Halprin Associates –

How the Sculpture Clock Idea Was Born

Correspondence between Thomas E. Brown, Principal with Lawrence Halprin and Associates, and sculptor Jack Nelson was discovered in the Halprin Collection at the University of Pennsylvania. The letters, dating from March 13, 2021 (during the early design of Nicollet Mall) to November 8, 2020 (after Nelson’s installation of the Sculpture Clock) reveal a collegial and affectionate relationship. The back-story is uncovered in additional correspondence between Richard Vignolo, Halprin and Associates, and George Barton, Barton-Aschmann Associates, the lead firm in charge of the Mall’s construction.

The Sculpture Clock project for Nicollet Mall in Minneapolis was Nelson’s second opportunity to collaborate with Lawrence Halprin and Associates. During the 1960s, Halprin’s firm was doing a lot of work in Syracuse, New York. Thomas E. Brown, one of the principals, became friends with Nelson, a sculptor teaching in Syracuse University’s College of Fine Arts in the School of Architecture.

In early 1964, Brown proposed to his client Raymond D. Nasher, banker and real-estate developer of the NorthPark Center in Dallas and dedicated collector of Modernist and contemporary sculpture, that Nelson create what Brown described as “a sculpture clock apparatus.” The firm had designed the frame or case for a clock that would be a centerpiece of the shopping center and Brown thought Nelson was the ideal choice to create the sculptural components within it. The client thought it a “rather weird idea” and over time, the project did not materialize. But Brown held out another possibility to Nelson – to create a second one in Minneapolis.

The September 14, 2020 letter from Vignolo of Halprin’s office offered Barton several thoughts about art for Nicollet Avenue, including a sculpture clock:

In regard to the sculpture, Larry [Halprin] and I have had serious discussions about it and have reached the following decision and would like your thoughts on this matter. We have come to the conclusion that all the sculpture must be purchased pieces and not commissioned. Recently on several jobs where we have commissioned sculpture or other art either ourselves or the client in the end were disappointed and, throughout, the evolution, misunderstandings of the design intent developed. The client particularly had difficulties in visualizing the finished product from sculptors’ generally lousy sketches. The public nature of Nicollet Avenue I’m sure will confuse the issue even more.

We have decided that two large important pieces are all that we need. We have considered adding additional smaller pieces as discussed with you on the last trip. However, smaller pieces seem not to work into the design, will detract from major pieces and possibly be more susceptible to vandalism.

We feel at least one piece should be by a sculptor of international repute. The best site for this is the block between 7th & 8th at Dayton’s. As you know, Don Dayton particularly wants a Henry Moore (in fact his store gallery has some for sale) in front of Daytons.

The other piece should be by a nationally or regionally known sculptor, preferably the latter. Larry will also discuss this with Don Dayton as he is knowledgeable as well with local artists through his gallery. It is also probably advisable for us to contact the director of the Walker Art Center.

We also have two clocks on the street. In the one in front of Rothschild’s we want to have a decorative element suggestive of the movement but really sculpture.

We are presently doing a clock similar in character with the sculpture portion designed and fabricated by Jack Nelson who is unique in devising moving sculpture. He is in New York and we propose using him on this.

Insights Into the Design Process

On October 12, 1964, Brown wrote Nelson, enticing him to work on the Nicollet Mall project:

I am writing now to set in motion the gears and escapement devices in your head on creative cogitation for a mate to the Northgate clock. We are starting on the Minneapolis downtown project and I’m pushing for another Nelson clock… and am quite sure that it will work out. So, at this point I’d like some thoughts on what you’d like to do – how to work it out with another one, how much to duplicate, what changes you’d like to try, etc. etc. I’d imagine that it could well be the same clock and we could capitalize on the duplication of the parts and so forth, as they are half a continent apart. However, if the location on a city street corner, the character of the buildings adjacent, or simply your own desire to try something different suggests some changes to #1, that’s fine with me… In about a month we’ll have run a definitive total project cost estimate and then we’ll know if we can afford this or not, but at present I can believe we can.

Scheduling is pretty tight, and at present breaks down as follows: Our drawing, with all costs, are to be completed Feb. 1, 1965. Construction begins in March, with completion November 1, 1965. So your shop work could begin any time we get approval, with assembly in Minneapolis sometime in October 1965.

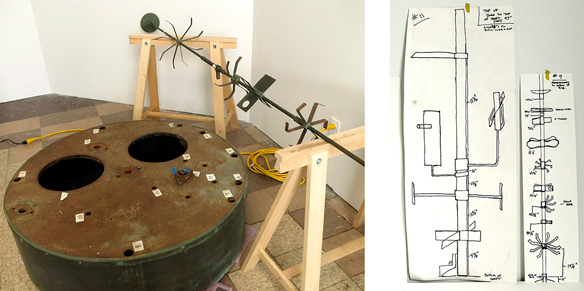

Proposal sketch for the Sculpture Clock

Nelson replied to Brown enthusiastically on October 16, 1964:

… After looking over the sketches (nicely done) I’d like to counterpoint or fugue so to speak with the up and down feeling of the architecture on that street, and play around with the feeling of horizontal movements of the traffic, both cars and people. It is a different environment than Northgate and my feeling is it should be a sculpture for its own environment. Some of the basic elements can be duplicated, but my feeling as a sculptor is that each piece should be original and related as much as possible to the architecture etc. that surrounds it… I honestly feel strongly about making sculpture for architects, not just decorations.

To point a fact, in Sweden I turned down a commission because I just could not relate to the building in the manner that I work. It was a great old railway station (in Dalarna, I believe). I liked the building (by old, I mean not contemporary, but not historically old either) and I suggested that they get a sculptor that worked more representational. They didn’t understand and I thought I was coming on like a big deal American, but I just could not see my work in front of that place. It would just have been a mutual satire and nobody would have been happy with it.

Later on December 10, 1964, Brown responded:

… Nicollet is shaping up but still some problems to resolve. First is obtaining a commitment from the city (this is a public project subject to bids, as differentiated from Northgate) that certain “contractors” will definitely be employed (yourself plus another artist we’re using on fountains) and getting initial final allocation to assure this.

We’re still going to use the 4-face clock and the frame is still 5’ square by about 14’ high, black, glass cased… Your thoughts on the movements – a sculpture for its own environment – is certainly right to us too. The one point Halprin made is that he’d like the sculpture pretty much a unity – like one material or basic texture – fairly solid seeming – in short a pretty sophisticated thing in keeping with the over all clock concept. …if you’ve any further thoughts on this one in terms of overall mass and character rather than the movement quality itself – the first glance impression one gets – we’d appreciate some words or a sketch about it. It may affect our design of the case. By all means any other thoughts you have relative to scale, unity of your works with ours, etc. we’d be happy

to have.

Complications, Arrangements and Completion

Six months later, on July 6, 1965, Halprin’s office wrote Nelson spelling out the terms of his contract: he would be working under a contractor who would be building all of the “special features” including the frame, doors and clock element for the Sculpture Clock. Brown said, “we finally decided to have him simply make an allowance during his bid period for your work, and then contact you for all coordination, timing, and financial arrangements. Your contract would be signed with him and he will be responsible for completion of the whole thing, and is to provide whatever installation assistances you will need.”

However the entire Nicollet project was experiencing delays and complications that sound remarkably contemporary. According to Brown:

… our glorious project has plunged into the mire of bureaucratic harassment again, this time in the person of multiple assessment problems. … our many clients are true to form in declaring their particular portion of the total cost to be greater percentage-wise than their particular benefit derived. They are, however, all still in favor of the project itself as we have detailed it – and we expect the cost wrangling to be smoothed out eventually, although not soon enough for construction to begin this year. So – the best guess that I can make at this stage is for an early start Spring ’66, and hopefully the new mayoral election, wavering stock market, spring flooding and Viet Cong activities for the next 8 months are not enough, in combination, to bring the whole Grande Scheme to a final shuddering halt.

The following year, on March 2, 1966, Brown wrote they had, “just received the long-awaited and somewhat astounding news that the dauntless and intrepid Nicollet Avenue merchants have agreed to go ahead with the project” and that Nelson should expect the contractors to be in touch with him when the bids were received. In this same letter, Brown announced in a post-script that, “It looks like the Dallas NorthPark job is dead – Ray Nasher is out of funds.”

Over a year later, on May 12, 1967, the Minneapolis City Council unanimously authorized Nelson to furnish the clock sculpture within a budget of $9,480 (around $68,000 in 2016 dollars) and directed the City Purchasing Agent and City Engineer to execute a contract with the artist. However, the City contract was slow to materialize and Halprin’s office nudged things along. On June 23, 1967, Vignolo wrote Senator Harmon T. Ogdahl (Minnesota legislature, District 37, 1963-1972, and Executive Vice-President of the Downtown Council) asking for an advance of $3,160 to enable Nelson to purchase materials and get started. The letter assures that the advance will be reimbursed with Nelson’s initial payment from the City, as per his contract, and that Halprin & Associates guarantees the repayment of this sum on behalf of Nelson. The firm goes on to vouch for the artist’s reputation and ability, stating that they “consider that he is the only person qualified to produce the sculpture.”

That same day, an Assignment of Contract Payment was entered into between Jack Nelson (Assignor) and the Downtown Council (Assignee) awarding Nelson a contract for “the construction of a clock sculpture for the Nicollet Mall in the amount of $9,480.00.” In order to perform said contract, Assignor must “expend moneys for premium on contract performance bond, and for the purchase of necessary materials and equipment for the construction, fabrication and installation of the clock sculpture.” The contract details the advance of the first installment of $3,160 referred to in the letter from Vignolo. The contract was signed by Nelson and Ogdahl and documents show that a check for $3,160.00 was sent to Nelson via registered mail on July 3, 1967. It appears the Downtown Council rather than the City contracted with the artist.

Nelson is defined as “contractor” and the agreement states: “The Contractor covenants and represents that he is a professional sculptor and designer, with special qualifications and experience in the field of designing, fabricating and sculpturing the object described in said specifications.”

The agreement continues, “the work of the Contractor shall include the construction, fabrication, sculpturing, assembling, and installation of all of the parts of the completed object, including drive mechanisms, motors, all necessary switches and controls, and all necessary bolts and connections; all to be installed in the completed clock structure in the final location on Nicollet Avenue, Minneapolis; and shall include final inspection, testing, and verification of the satisfactory installation and operation of the completed project. It shall include the furnishing by the Contractor of all materials required for the completed project, and all costs for the use or hiring of necessary equipment used in the process of fabrication, construction and installation.” The value of the agreement is $9,480 and it specified three progress payments of $3,160. Peerless Electric, world-class designer and manufacturer of specialty AC and DC electric motors (still in business in Warren, OH), fabricated the clock and its case under a separate contract.

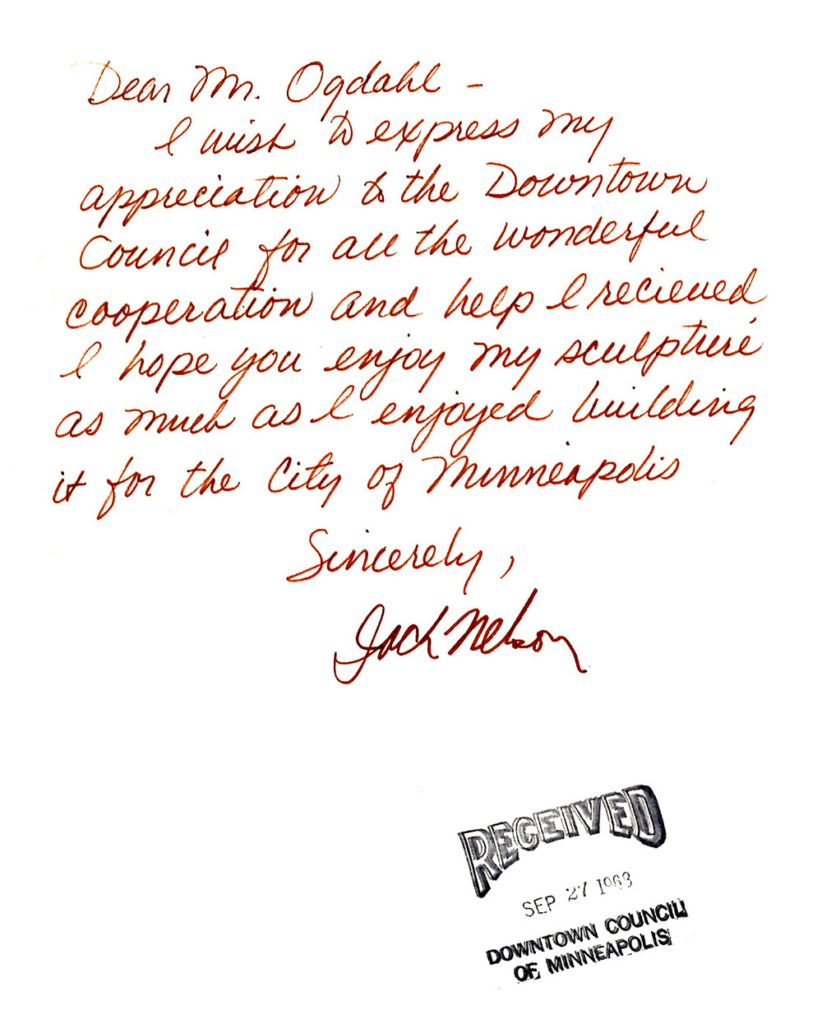

On September 27, 1968, after City personnel installed the work on the Mall on Nelson’s behalf, he sent a personal note to the Downtown Council. Nelson thanked them for their wonderful cooperation, and the help that he received and said he hoped that they would enjoy his sculpture as much as he enjoyed building it for the City of Minneapolis. This handwritten note was on the back of a poster for an exhibition of Nelson’s work at the Oscar Krasner Gallery in New York City.

Personal note from Jack Nelson in 1968

The Downtown Council announced the clock’s dedication in a press release on October 7, 1968. It mentioned that the work includes over 500 separate pieces that were designed and assembled into this unique art work which was a year [!] in the making. The Star Tribune featured a photograph of the unveiling of the clock by Downtown Council and Young Quinlan Building executives and Kim Adams, Miss Downtown, who bears an uncanny resemblance to Mary Tyler Moore, although that TV show wouldn’t appear for two more years.

Star Tribune, October 1968

The following year, O.D. Gay, new Executive Vice President of the Downtown Council wrote on March 6, 2021 to Ron Haselton of the Worcester (MA) Five Cents Savings Bank, an admirer of the clock and described it thus:

The following information will be of interest to you: The clock that has been installed on the Nicollet Mall is 16 feet high and 5 feet square. It is constructed of steel columns with 1/2 inch unbreakable glass on all four 12-foot high sides. The clock face itself is 4 feet high and there is an individual clock on each of the four sides. The clocks and housings were made to our specifications by Peerless Electric Company of San Francisco, California. The cost was $12,237.00 for this part. Within the base housing for a height of 12 feet is a perpetual motion mobile driven by four small 1/3 horsepower motors. Mr. Jack Nelson, professor of Architectural Design of Syracuse University constructed and installed the mobile [sic]. The cost of the mobile [sic] was $9,480. The clock was designed by Professor Jack Nelson, professor of architectural design at Syracuse University. He also designed the mobile [sic] beneath the clock. The clock was built by Peerless Electric Company, San Francisco. It cost in total including clock, housings and mobile [sic] $21,717.

Should the Sculpture Clock Return to the Mall?

The iconic Sculpture Clock has admirers and fans and Nicollet Mall visitors have fond memories of it over the years since it was installed in 1968. One of its greatest supporters is Rosemarie McDonald who has lived in a condominium on the Mall since 1978. On September 17, 2013, she wrote the Nicollet Mall Design Team a letter that said, “My hope is this unique 45 year old historic piece can be brought back to life on the new Nicollet Mall and provide enjoyment for years to come before time takes its toll and the deterioration becomes too extensive and it is lost forever.” A self-proclaimed “Friend of the Whirligig Sculpture Clock,” she always found it fascinating to watch kids, young and old, stop and watch it perform.

In 2014, the City of Minneapolis was considering what to do with the existing public art including the Sculpture Clock and decided to conduct an on-the-street survey. From June to November, evaluator Rachel Engh and a team of assistants were positioned at each of the eight artworks. They asked passersby: “To what extent does City-owned permanent public art stimulate excellence in urban design; enhance community identity and place; and contribute to community vitality?”

In total, 509 people were surveyed and the Sculpture Clock had 71 responses. Nearly all of them (90%) believed the Sculpture Clock contributes or adds to the place where it is located. Some commented that as a clock, it was useful and functional – if not always accurate – and it served as a landmark, anchoring the Mall. Others said that it adds beauty and reflects history, and two thirds (66%) said they would miss the Sculpture Clock if it were removed from the Mall.

During the three days that art conservator Kristin Cheronis and her team were inspecting and disassembling the Sculpture Clock on the Mall prior to the beginning of construction, dozens of people stopped to tell them their memories. When Mary Altman, who directs the City’s public art program, posted a call for information about the Sculpture Clock on the Historic Minneapolis Facebook page, she was surprised by the outpouring of personal reminiscences. She even received a grainy 8mm film from the early 1970s showing the clock in action.

It became clear that the Sculpture Clock is valued not only a unique example of mid-Century Modernism, an early artist-designer collaboration, and a rare kinetic timepiece, but also because it is beloved and provides continuity with the Mall’s past – and people hoped it could be restored.

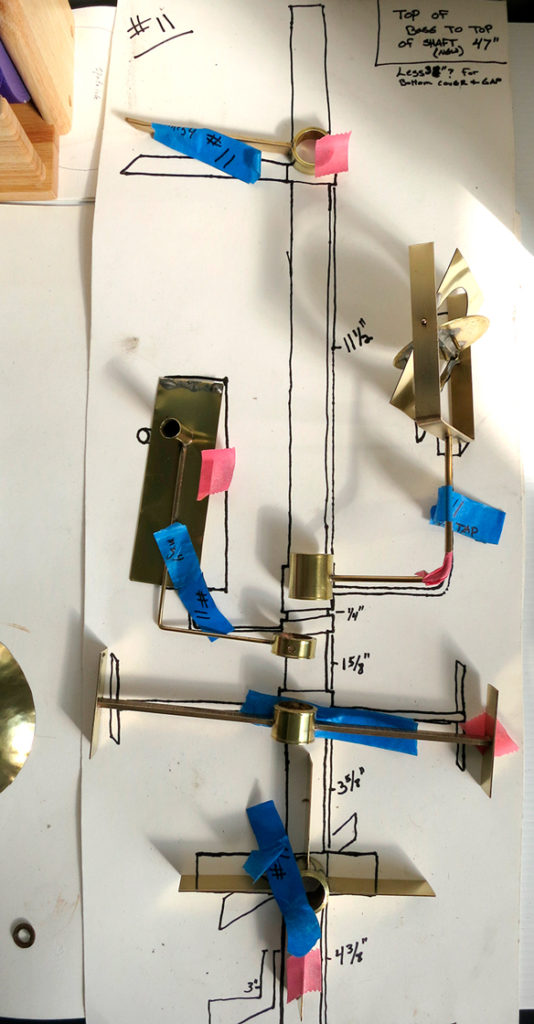

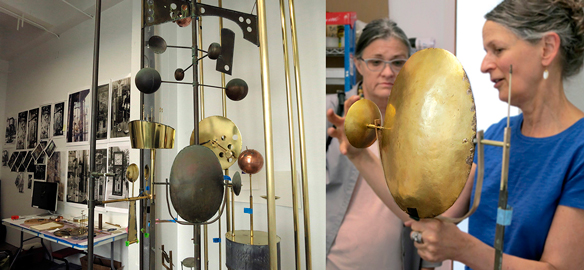

Eleven foot tall sculpture with more than 511 parts. Shown in artists’ studio during fabrication.

Restoring the Sculpture Clock – What Would It Take?

Kristin Cheronis is a professional conservator and a member of the American Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works (AIC). Conservators are devoted to the preservation of cultural property for the future. They have graduate-level training in art conservation; credentials from the AIC; and follow a code of ethics and standards. They examine, document, treat, and provide preventive care, supported by research and education. Kristin has made a specialty of conserving outdoor sculpture and contemporary public art and is nationally recognized for her expertise; we are very fortunate to have her working here in the Twin Cities.

Her first step was to examine and document the Sculpture Clock, producing a condition assessment, and then to prepare a proposal for conservation treatment and restoration, including a budget.

According to Cheronis, the artwork has two aspects: it is a street clock with four large dials in the upper cabinets of the case and it is also a kinetic sculpture – or as artist Jack Nelson called it, a “perpetual motion stabile.”

Cheronis’s technical description of the artwork follows:

The Street Clock includes a 16-foot-tall case built by Peerless Electric out of exceedingly durable materials. The main structure is thick, heavyweight, galvanized steel; the tightly-fitted moldings around the glass are made from high quality architectural bronze; the large windows are ½” thick glass; the handles and hinges are solid, cast bronze. The clock dials are white sheet acrylic, which allows them to be illuminated from the back and the hands and numerals are lacquered bronze. All of the original electric components (clock motors, sculpture motors, lighting) were high quality and selected to be durable and maintainable, and also low maintenance.

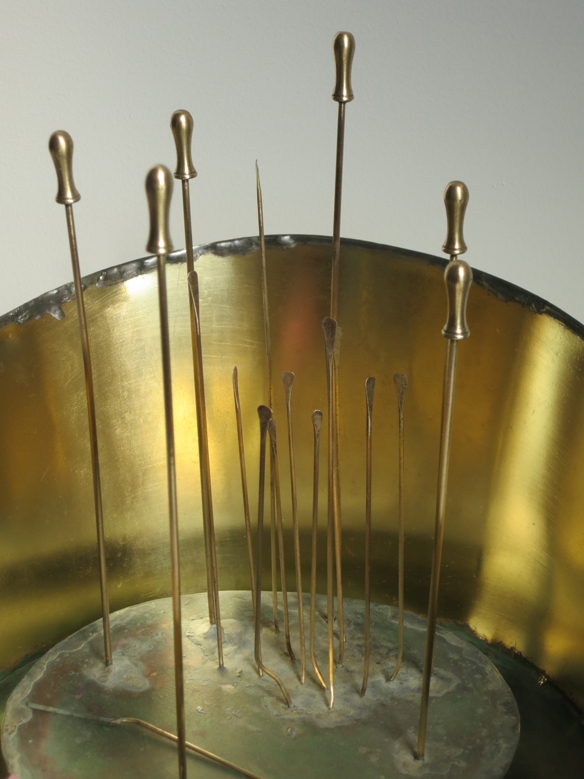

The Sculpture Clock within the glass enclosure is a large, “perpetual motion mobile;” a handmade brass mobile sculpture made by Jack Nelson. The work is fabricated from brass and copper primarily, with the addition of some mirrors, steel springs, bouncy metal straps, etc. The 11-foot-tall sculpture is composed of more than 511 parts, with an additional 307 hardware elements, for a total of 818 parts. The sculpture was designed to be installed in the lower portion of the case, and to remain in “perpetual motion.”

Nine stationary shafts and five rotating shafts have sculptural attachments such as hollow floats, star-shaped wheels, bouncy straps and springs, swinging spoon-shaped elements, mirrors and more. Five motors operating at three different speeds rotate the five shafts. An additional double-ramped cam mechanism causes two half-height shafts to hop up and down vertically. When in motion, the various whirligig-like elements installed along the shafts interact with each other playfully; twirling and swinging, swaying, jumping and jiggling.

Nelson assembled the hundreds of components from a combination of ready-made materials (brass pipe, copper toilet floats, round mirrors in frames) as well as hand-fabricated components. He created many of the individual sculptural components from scratch using sheet brass employing standard metal forming and assembly techniques including bending, cutting, brazing, chasing and some repoussé. Originally, all of the elements were highly polished to a bright finish; free of patina, coloration or tarnish.

Detail of Sculpture Clock in Jack Nelson’s studio during fabrication.

Bob Schmitt and Ray Haynus from the City of Minneapolis Department of Public Works and Jesse Ossendorf of the Downtown Improvement District (DID) all have been involved with maintenance of the Sculpture Clock sometime during the past 46 years. Cheronis interviewed them and found that the kinetic sculpture was in operation from 1968 through 2002 – an impressive run of 34 years! The clock portion ran continuously until it was de-installed in 2015.

The perpetual motion sculpture’s motors only required infrequent repairs. The most significant problem was that cold winter temperatures could cause the grease to stiffen in the motors and gears and the impeded movement and friction strained the motors. They would repeatedly stall and start up, overloading and wearing out the motors. On several occasions, the lack of lubrication or grease caused parts to seize up and break as the motors continued to drive the shaft. The maintenance crew reported that when this happened, they would usually allow the single damaged shaft or motor to remain non-functional for the winter and then repair it in the spring. The rest of the motors and shafts would continue to function, without significant loss of visual interest to viewers, until it was repaired.

In 2002, the last estimate for new motors was presented to the City which declined to order them, due to cost. (The motors cost approximately $350 each at that time.) In 2004, Ray Haynus had his crew polished all of the brass for the last time. In 2008, the care of the clock was handed over to the Downtown Improvement District and since then, no work has been done on the sculpture.

Cheronis says the Sculpture Clock is in poor condition, overall. The case and sculpture enclosure is in fair condition but all of the weather-sealing gaskets are badly damaged and failing and the roof leaks. The steel is rusting and the paint is peeling. The mobile sculpture itself is in very poor condition: the motors are not working; the mobile elements are not moving; there are breaks, bent sections and missing elements. All of the metal elements are corroded and tarnished.

In her estimation, the Sculpture Clock is the highest conservation priority in the City’s collection of public art. It is in the worst condition of all of the 64 artworks the City owns; it has not received any care since 2002 and it has never been professionally conserved. Without care and conservation, it cannot be returned to the Mall – and an important part of the City’s history would languish in a storage warehouse, inoperable and unseen, deteriorating further.

This highly complex, mechanical artwork operated and functioned successfully for 34 years. Cheronis says that Nelson designed it to operate and function reliably for the long term, fabricating it with sufficient integrity to achieve a significant lifespan. She believes that if it were repaired to working condition, and if it received regular maintenance and occasional repairs, it could be expected to last at least another 30–40 years. She estimated the cost for restoring the Sculpture Clock including the case, the sculptural apparatus, and the timepieces would be $261,000.

Conservation of the Sculpture Clock was proposed to the Minneapolis Arts Commission. The Commission and the Minneapolis City Council acknowledged the historic and artistic importance of this Minneapolis landmark – and determined it should be conserved and returned to the Mall. The City submitted a grant proposal to the State of Minnesota and in November 2016, was awarded $92,948 from the Arts and Cultural Heritage Fund through the Minnesota Historical Society, enabling the restoration process to begin.

Restoration of the Sculpture Clock has been financed in part with funds provided by the State of Minnesota from the Arts and Cultural Heritage Fund through the Minnesota Historical Society.

Photo Essay - Restoration of the Sculpture Clock Part 1, Spring 2017

Jack Nelson’s Sculpture Clock new and shiny on Nicollet Mall in the 1970s (left) and rusted and inoperable in the conservation studio in 2016 (right).

Jack Nelson’s gleaming kinetic Sculpture Clock engaged passersby on Nicollet Mall in the 1970s. Inactive since 2002, dusty and corroded and with broken and missing pieces, the work was de-installed prior to the start of construction on the Mall in 2016 and moved to the studio of sculpture conservator Kristin Cheronis in Northeast Minneapolis. Our region is fortunate to have Cheronis, one of the few professional conservators nationwide who specialize in outdoor public sculpture, particularly contemporary works.

Cheronis assembled a “clock team” including Laura Kubick, sculpture conservator; Rory DeMesey, mechanical specialist; Max Cora, talented metal sculptor who will take on structural repairs; Susan Wood, clock restorer and kinetic sculptor who will restore gears and undertake polishing duties; and kinetic sculptor Norman Anderson, kinetic movement advisor.

Cheronis references blow-ups of the photos taken by artist Jack Nelson as he constructed the artwork in the late 1960s. One wall in the restoration studio is entirely papered with photos of the Sculpture Clock taken from various angles and close-up.

“Conservators almost never get this lucky! I know of no other instance where such detailed information was available about a work of art,” Cheronis says. “We had several big gifts. Excellent photographs of the installed artwork were discovered in the Lawrence Halprin collection in Philadelphia and most amazing was a trove of materials saved in the artist’s widow’s garage – original photographs, detailed blueprints, and documentation of the fabrication process at Nelson’s studio. Historic movies showing the sculpture’s movement were provided by members of the public and also discovered in the KSTP archives at the Minnesota Historical Society. Miraculously, the City had saved all of the artwork’s motors. We’re ecstatic to have these materials.”

Rosemarie McDonald, long-time Sculpture Clock advocate and Nicollet Mall resident, helped the clock team find critical film footage. She suggested that Mary Altman use social media and post a call for information on the Historic Minneapolis Facebook page. Rosie L. Riley of Witchita, KS responded to the post by providing a brief home-movie clip. Diligent research by Cheronis’s team also uncovered old movies from KSTP television at the Minnesota Historical Society. These rare finds provided clues to the sculpture’s movement, showing the Sculpture Clock in motion from all angles. Kristin Cheronis, Max Cora, metal sculptor and restorer, and kinetic sculptor and advisor Norman Anderson discuss the film footage with McDonald.

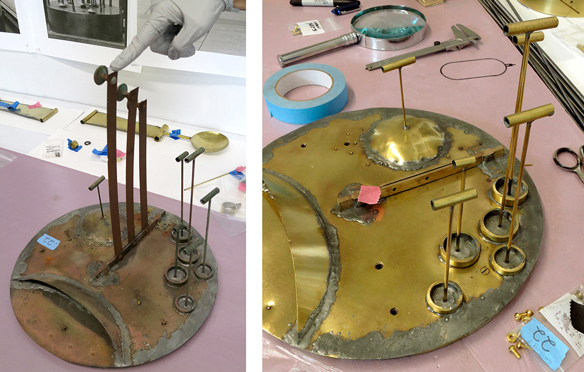

First came disassembly of the sculpture. Cheronis and team devised a system to identify and catalog each part so that it could be repaired or replaced, polished and reassembled. The Sculpture Clock has over 900 existing parts and more than 40 missing parts. This was a critical and daunting task. The team often gave names such as “The Hopper” and “The Spiny Basin” to some of the assemblies in order to identify and talk about them. Here, disassembled Shaft #11 has parts removed for repair, cleaning and polishing.

Max Cora is repairing and restoring parts and in some cases, reinforcing and even recreating worn-out or missing parts. Here, a bearing joint that is completely worn-through, bent and broken, that must connect cross-bars and also allow a supporting shaft to rotate, is being re-created. Cheronis and Cora consult historic photographs to determine how the joint was originally shaped and how it must connect the crossbar to the support arms.

Elements nicknamed the “hopper.”

Susan Wood, a clock maker who builds clock mechanisms and repairs antique clocks, is very detail-oriented and particularly skilled in working with fine, small parts. Both Wood and Cora have worked with Cheronis for over twenty years. Wood is polishing one of the parts of The Hopper. Her three main polishing tools: by hand with small pieces of polishing pads; a polishing bench lathe; and an arbor with custom-made pads.

Cheronis shows Altman the results of polishing efforts and the remaining structural repairs that are needed on a particularly detailed and fragile assemblage with cast hat-pin forms which the team has dubbed The Spiny Basin. She holds it up to show its location within the Sculpture Clock composition. You can also see The Spiny Basin in two photographs of the sculpture that lead off this photo essay.

Laura Kubick is restoring the 104 bronze numerals for the clock face. Each numeral is 6 inches tall. She uses a series of polishing pads to remove corrosion and old coatings and then lacquers the bronze to re-seal it. The numerals will be reattached to the four white sheet-acrylic clock faces.

Conservators often must improvise special tools to clean and restore works. Here they make swab-like tools out of steel wool and toothpicks to clean corrosion out of the holes in a perforated steel cannister known as The Hopper. It’s painstaking work and Cheronis and two conservation assistants, Nicole Flam and Abby Slawik, tackle it as a team, cleaning out each tiny opening with quiet concentration.

Original photographs by Regina M Flanagan during Clock Studio visits December 2015, and March and April 2017.

Photo Essay - Restoration of the Sculpture Clock Part 2, Late Spring & Summer 2017

Sculpture Clock prior to treatment (left), removed from its case and disassembled in the conservation studio. On the right, note the stark contrast between the first few elements that have been repaired and polished, and the dull, tarnished and bent elements awaiting treatment.

The shaft with a pillow-like form, crudely repaired many times, had extensive structural damage (left). After repair and polishing (right), the pillow form gleams.

The circular riser housing the motors that turn the shafts is awaiting treatment (left) along with a side shaft. Before disassembly, each shaft was carefully documented in photographs, and drawings detailing each assembly included measurements (right).

Many parts were completely worn-through from friction and abrasion, and old bearings were inoperable (left). New bearings (center) were custom-fit with frictionless high-tech iGOS components (white spacer visible between metal parts). Several missing copper float forms (right) were recreated from studying historic photos of the Sculpture Clock, and spun from copper by Michael Johnston.

Ceiling component (left) prior to treatment shows extreme galvanic corrosion from adjacent incompatible metals. During treatment (right), elements are removed for repair.

The mechanically complex self-referencing clock form (left), had been altered and damaged. Susan Wood, the clock maker on the conservation team, oiled and re-built the damaged parts (center). A photo of the same form taken at the artist’s studio in the 1960s (right) provided critical guidance.

75% repaired, polished and reassembled! This video shows a movement test in the studio.

An array of parts and shafts after repairs, reforming, and polishing (left). One of Jack Nelson’s many whimsical hand-crafted pieces is on the right.

After repair and polishing, parts are ready for reassembly, except the rusty, complex dish form with vertical hatpins (middle right) which awaits attention.

The spoon-like forms had completely seized, causing the brass rod to buckle and collapse (left). After structural repairs and polishing, they swing freely again (right). View them in this video.

An element that the team nicknamed the “hopper” during treatment (left), and functioning fully, nearly complete (right). View the composition of moving elements surrounding the “hopper” in this video.

Original photographs and videos by Regina M Flanagan produced during visits to the Sculpture Clock restoration studio in May and July, 2017.

Watch for future posts this fall documenting the Sculpture Clock’s return to Nicollet Mall. You may sign up to receive notices here.