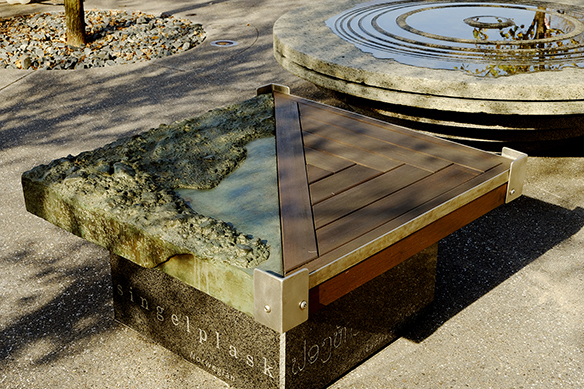

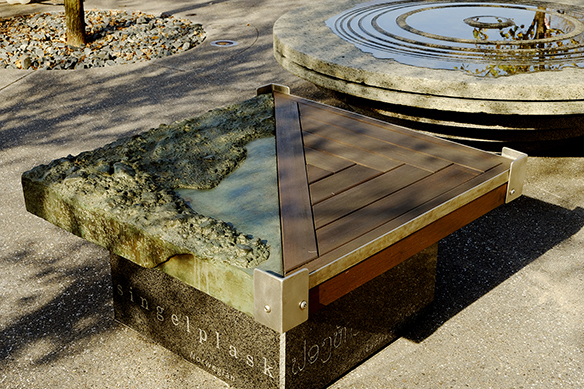

Worker seals the wood seating surfaces of Enjoyment of Nature preparing them for winter. The ethic of care is important to artist Kinji Akagawa.

I had the pleasure of discussing placemaking and public art with artist Kinji Akagawa, creator of Enjoyment of Nature, at his home and studio in Afton, Minnesota on November 3, 2017. For 36 years, Akagawa was a devoted teacher at the Minneapolis College of Art and Design. In 2007, he was honored with the McKnight Distinguished Artist award that recognizes artists who have chosen to make their lives and careers in Minnesota, making our state a more culturally vibrant place. He is widely-respected and one our state’s treasures. Known for his philosophical nature and inspiring capacity for free-association, I’ve tried to capture his remarks with fidelity in the following text from an audio recording.

Regina Flanagan: I’ve been pondering the topic of placemaking and writing down thoughts for over a year; considering it relative to public art and the Nicollet Mall project. Your work has been involved with placemaking from the start in the 1980s. Given where we are right now, how do you respond to the current notions of placemaking?

Kinji Akagawa: At the beginning, the idea of placemaking was an offshoot of public art involvement. (A response) to plop art that didn’t work; to what “public” means (as distinct from) “private” art from the studio; to “no, no, no, it didn’t work;” and controversy and money pulled out. Artists (at first) didn’t understand what “public” means. Ideas of art are totally different in American and European traditions. In a democracy, from the beginning, we are connected because of culture and history.

RF: Because we’re diverse?

KA: We are not all pure black or white. The Zen idea is that we were all monkeys once. (Laughter.) That’s the starting point – none of us are independent; it’s all about interconnection. My seating projects (including Nicollet Mall and the Minneapolis Sculpture Garden) are influenced by (philosopher) Martin Heidegger’s building, dwelling, thinking. That making something is both cultural and social.

The words “pebble splash” are featured in eleven languages: English German, Norwegian, Swedish, Spanish, Hmong, Laotian, DaKota, Gaelic, Polish and Vietnamese, honoring the people who Akagawa calls the “city-beginners.”

RF: As an artist, art-making moves through you – and the circle is completed by the people who receive the work and interact with it. The work of public artists is about communication. From early on, public art was about use or purpose, as well; which is what attracted me to the field.

KA: Like (philosopher) Ludwig Wittgenstein, if philosophy is not useful every day, what use is it? (Laughter.) Applied art or craft or design – we have forgotten. Intellectual life is not based on language, but on physical life: music, dance. Without it, there’s no quality of life! They are useful! In church we sing, we mourn, and write poems.

I accept the temporalness of my life and of art. I don’t expect aesthetic experience to be static and permanent, but dynamic. Makes everyday life joyful, shareable, loveable.

RF: I was considering whether placemaking is a verb or a noun; an action/activity or the resulting object/thing. Obviously, it can be both. But what you’re telling me is that in its most democratic condition – it’s a verb.

KA: Synergistic experience, that’s the desire and hope; shareable. In our world, if diversity is accepted, we can talk. (There’s a) circular interdependence of language. Artists made a mistake to separate mind and body. Giotto (and other early painters of religious subjects) connected with sentiment. Linguistic and emotional intelligence can be separated, but seeing the being in the face in the mirror like Rembrandt (when he painted his self-portraits), we are compelled to bring out empathy, and then aesthetic connections. That’s the condition. Placemaking is not a physical object.

At a conference in 2006 (where I served on a panel), we talked about the egotistical self. We want to know each other’s experience and the external world. We have to say “we hate it” and see how others react.

RF: Defining oneself through relationship to others.

KA: From egotistical self to ecotistical self. That’s the transformation to adulthood. We’re interdependent and can find ourselves in others. Some people never experience ecotistical self. It’s just all about ego and economic life; so concrete, nothing open.

RF: The egotistical person sets up their boundaries and won’t let others in. Consequently, that person won’t understand things outside their self-imposed boundaries.

KA: Self-expression is taught at art school…

RF: Self-expression is the tiniest part of the whole public art dynamic.

KA: Social expression, self expression, cultural expression; all need to happen so we understand each other. Ecotistical self is a compounded self; no longer one identity. I am part of everybody else. If you do not use language that’s shared by the community, no one will understand you. Language is shared and part of human ecology. Ecotistical self; no one can teach you. It’s a transformation (you must make).

Shifting the focus from maker to relationship… I’m just like any other worker. (We) share economically, socially, culturally. The more relationships we have, the more enriched and shared is our life. Artists in order to be dynamic, look for new relationships. Looking authentically, putting the self out and looking for new relationships; (to gain) new understanding, not just to have me understood by others.

Placemaking is not the idea of the territory of an object. It is the metaphysics of caring.

Enjoyment of Nature is for humans and our feathered friends.

RF: For the past year, I’ve been writing about the art on Nicollet Mall which includes a great arc of types of public art… From Jack Nelson’s hand-made Sculpture Clock of the 1960s to Tristan Al-Haddad’s recent work that goes from sketching to computer to model-making and then, the attendant difficulties of fabrication. …What it takes to create something, and the placemaking piece, and finally, the experience of the work once it’s installed.

All three new works are phenomenological and almost need no explanation. People will write their own narratives about them. They present a new experience within the spectrum of public art experiences. That’s kind of the time period we’re in right now – where everyone writes their own story about things. Everything from the evening news to the blog I’m writing uses a storytelling mode which has the potential to be subjective in an unhealthy way.

KA: I don’t know everything, but by talking, I can find something meaningful. This is the potential. This is the idea of dialogical stuff. One opinion (compared) to the other is not dialogical; (it’s) my opinion vs. your opinion. This is alienating and separating. The idea of phenomenology is that inter-subjectivity is the key. Two monologues are not phenomenological. So already from the beginning in adulthood, I am an interdependent person. I have to be able to allow other worlds. (When the) brain is totally open; that’s inter-subjectivity. I’m glad that oral culture (storytelling) is coming back. Temporalness becomes meaningful.

Public art is democratic art. The teacher is basically a learner. The condition (and situation) determines who’s learning and talking. Knowledge has to be flexible from the beginning. Puzzlement is always a part of it.

RF: Many people would take issue with that because it requires a level of openness and the ability to handle discomfort and new information.

KA: Heidegger talks about a closed and open person. “Openly open” heart has no closure; “openly open” person doesn’t shut down, listens always. That’s the inter-subjectivity. That’s the plateau of inter-subjectivity. Everything is uncertain and gray in that level, but if there’s no understanding that way of being, there’s no concrete understanding of self as well as the other.

RF: In my twenties as I was growing up, I went through a period where I was aware of that and had to become comfortable with that kind of unknowing. It can be a psychological breakpoint.

KA: Nobody can teach you. You only become aware of that. That’s the kind of enlightenment, openness and awareness (I’m referring to).

RF: You just helped me to make sense of something, how many years later? (Laughter.)

KA: Without time, you don’t understand it. …Music, poetry. I recently heard this cellist and all of a sudden, the work got to me to me in a fantastically beautiful way.

Public art and placemaking: great, language-wise. But when we are talking, we have your definition and my definition; but there’s something else to it. I need to talk and listen. If so-called public art can function like that, it would be beautiful. Not public space or private space. Not separated from everyday activity but including making, doing, thinking – not separated – all interdependent. Why you do the work is to think.

RF: True, my photography is about curiosity; and the making of it compels me forward.

KA: Self-making and self-energy. Why do we all fall in love? Doesn’t have to be a person; it has to be a condition. There’s no reason. (Laughter.) It is my point of life. I crave more. When I hate something, why do I hate it that much?

RF: Sometimes the thing we hate, and our visceral response (to it), helps us define our feelings.

KA: Nonsense make sense! That’s in the linguistic world. (Laughter.) We all come through more (in our) aesthetic life, without separating science and life. Art should be air like that. Public art and placemaking; we are all in search of something.

Read here about Enjoyment of Nature created by Kinji Akagawa in 1992 for Nicollet Mall and its recent re-installation in the North Grove.